Sweet Thursday

A long walk about music criticism, context, and the album I've listened to the most in the last six months (and also John Steinbeck)

Hello again from Shooktown Review of Books headquarters. This is the first in what I hope to be a series of pieces about criticism specifically that I will put out over the next couple of months. In addition to these long things, I also hope to start putting out shorter, review-ier things that even have the gold star in reviewing culture–stars. This series of things will be called “Scalar Fallacies” and I will run the first one on Tuesday.

If you would like to read other things that I have written about old(er) books, you can read this piece that I wrote about Lydia Millet’s Oh Pure and Radiant Heart for Public Books.

Introduction

This was supposed to be an essay about whether or not people on the internet are too nice to Benson Boone. Sort of. Initially, as you will read, I wanted to write about Kelefa Sanneh’s piece in The New Yorker called “Everything Nice,” which was about the question of whether music criticism is too nice these days. As you will see, I find this to be a question that does not, as posed, totally make sense, but whose failure to make sense is provocative.

It provoked me, certainly, into writing a great deal of words over a great deal of time. It involves consideration of what the suitable contexts are for different kinds of creative work, and what people are actually trying to think about when they say that music is good or important. It also has several paragraphs about a John Steinbeck novel that is not directly about music. It is my first attempt at music criticism, I think (unless you count the piece I wrote about a sentence from “Weird Al” Yankovic’s Wikipedia page), and it stays about on track as you’d think, which is to say, not very. It is the first in a series that I hope to run here over the next few months about critics and the people they write to. It begins with my attempt to puzzle through what was going on with Sanneh’s article, from September of last year; it winds up mostly being about a bad called Sweet Thursday.

Statler, Where Is He? And Waldorf, Will He Live Forever?

One problem I had in writing about Sanneh’s article is not that it’s good or bad, but that its argument is somewhat muted, and developed alongside a set of claims that are interesting but not very polemical. I heard about the article because people online got het up about it: some people said actually yes, music criticism is too nice, and that’s why music sucks now; other people said that no, music criticism was too mean in the past, when Rolling Stone was smothering Andrew Ridgeley’s music career in the crib. Ultimately, this is a stupid framing. Asking if music criticism is too nice is like asking if food is too salty: some of it is, some of it isn’t, and trying to sort out an answer to the broad question is entirely unhelpful at the level of actual human interaction with this or that creative work or piece of criticism of it.

Sanneh is pretty on board with this, ultimately, I think. What Sanneh is getting at most crucially is a problem with the context of record reviewing. He notes that Rolling Stone got rid of its star-rating system in favor of just awarding some albums “Instant Classic” or “Hear This” stickers; but he also notes that they ditched those and brought the stars back. Calling George Harrison a “hoarse dork” (which Robert Christgau did, in his review of Dark Horse) or accusing Taylor Swift of being a dull billionaire are not really that important. The more important issue is how everyone else thinks about some ill-defined object called “music criticism” and whether it’s nice. The real problem with that is not so much a problem of quality as one of quantity. There is simply not enough music criticism being done at outlets who pay people to have the time to write about music, at the same time that people have increased access both to distribution channels, as well as ideas that tie something as seemingly ephemeral as pop music to serious issues involving race, gender or other identity categories or political concerns. “In this atmosphere,” Sanneh writes, “there can be no strictly musical disagreement.” There is not the proper context (whatever “proper” here will turn out to mean) for the music critic to do her task as it might have been understood in earlier historical moments.

This results in a mess: in the absence of a structure for critical dispute, judgments about taste have to mean too much (solemnly listening to Janelle Monae as a political act) or too little (insisting that no one can criticize your fealty to a Morgan Wallen song because your yum will not be yucked). Sanneh thinks this may be unique to pop music criticism, which already piles too many ideas from graduate school on top of a genre that descended from “Yes We Have No Bananas.” I’m not sure that’s true–book reviewing suffers from a similar cratering of a common background under which people situate their books. Sanneh also points out that the problems afflicting pop music criticism may relate to that music’s ubiquity–he notes that dance critics don’t seem to have this fake-nice problem, probably because serious dancers and their serious critics are in a more tightly connected, and thus coherent ecosystem. This pair of comparisons highlights one way of understanding the mess: pop music criticism does not happen in a proper context; in place of this, other (political or idiosyncratic) contexts are dragged in instead, and no one can adjudicate anything. Sanneh ends with a grim reference to Statler and Waldorf, from The Muppet Show: he points out his realization that for all their yukking it up at the expense of poor Fozzie Bear, they never criticize the human guests on the program. Even Statler and Waldorf have their criticism structured not in a context of shared listening to and understanding music, but by cultural capital. This is a problem, indeed. What can anyone do about it?

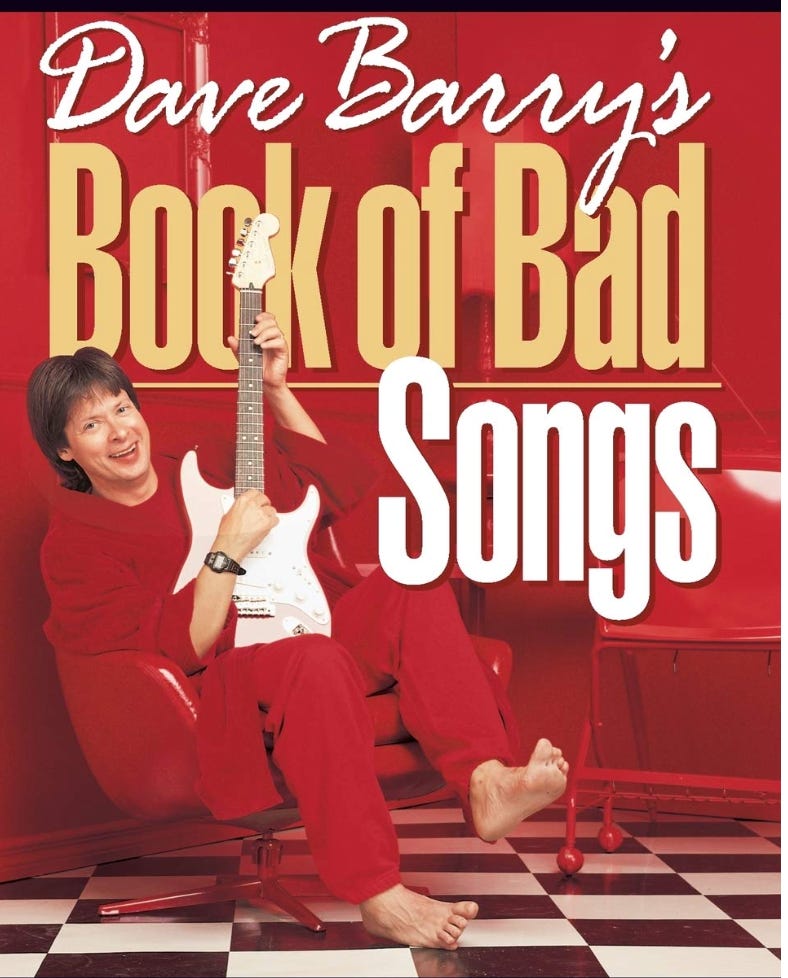

Dave Barry Is Not Nice

I turned, to answer this question, to Dave Barry. Whatever else Dave Barry’s Book of Bad Songs does, it is not deferential to the political or personal contexts in which the bad songs might be situated. I really hoped that Dave’s little book would help offer a useful different place to go from Sanneh’s essay, if only as a trove of sour comments from the Mean Old Days that Sanneh didn’t quote himself. Instead, what this drove home to me was the decontextualizing operation Barry performs in order to just write about how stupid the lyrics to a lot of songs are. The book should be called Dave Barry’s Book of Bad Song Lyrics. And, he’s mostly right. The problem is, many song lyrics are stupid even when they’re from good songs. “When the rain is blowing in your face/and the whole world is on your case/I could hold you in a warm embrace/to make you feel my love.” Say that in the voice Kenny Bania uses to explain Jerry Seinfeld’s Ovaltine joke, and it sounds dumb. (You need my embrace because the whole world is “on your case” and it’s raining?) Sing it, if you are Bob Dylan or Adele, and the words suddenly become the kind of profound thing that you can imagine being a hundred years old, or four thousand years old.

Some of Dave’s licks are good: he makes fun of Tony Orlando and Dawn, and he admirably has a chapter that’s all about the awfulness of demeaning lyrics about women. He says at one point that “Stairway to Heaven” would be better if it were forty five minutes shorter and didn’t have the line about the bustle in your hedgerow. “If there’s a bustle in your hedgerow, don’t be alarmed now” is, objectively, a goofy sentence; though I don’t know what sense it makes to take it out of “Stairway to Heaven.” The song would then be something else. “Stairway to Heaven” has been contextualized as a song that has a bustle in a hedgerow, for good or for ill. I listened to many of the songs that Barry makes fun of that I had never heard of, and he is right: they are pretty bad. But “Stairway to Heaven” is great. I decided that, with Dave’s help on this issue being non-dispositive, to follow a different thread presented by Sanneh’s article, which was his citation of Ellen Willis.

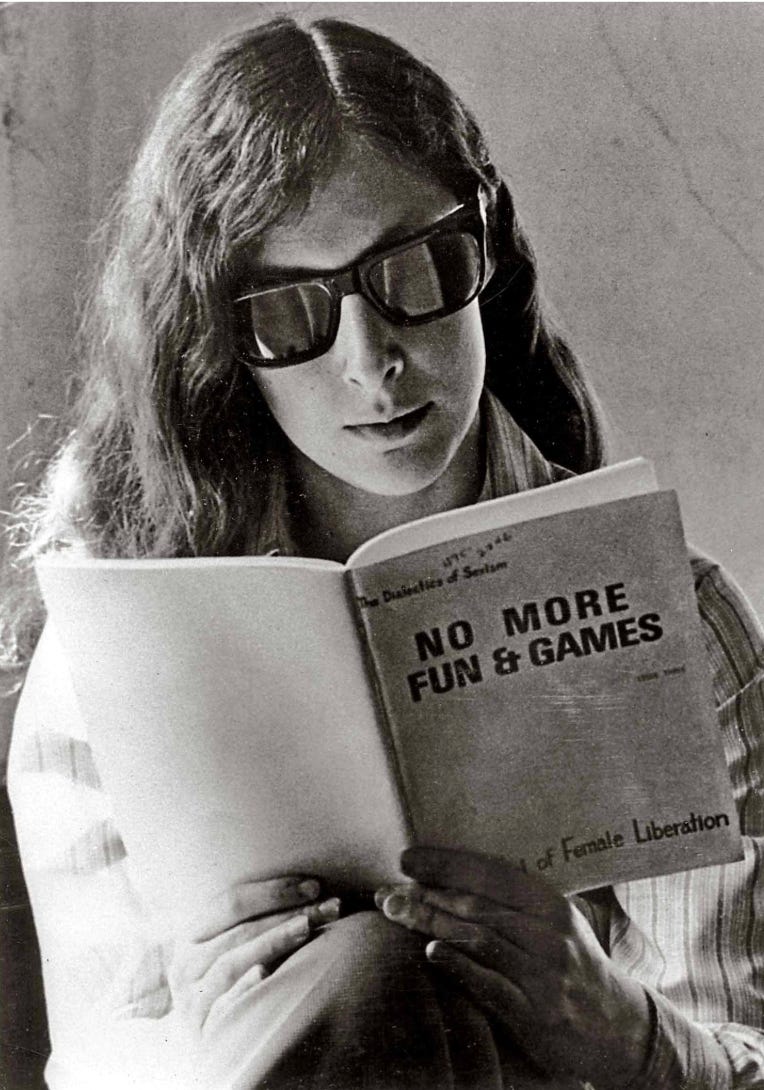

Ellen Willis’s Article of Good Songs

Ellen Willis is one of the greats. She was the first rock critic to write for The New Yorker. I have not investigated this but I assume that The New Yorker had, before hiring Willis in 1969, run a column every week in the back with the critical pieces that just explained for 800 words or so that another Cole Porter song was really good. Willis showed up and got them to start thinking about Bob Dylan and the Beatles and, especially, the Velvet Underground. Willis is one of the great appreciators I’ve ever read, and one of the things she appreciates the most is “Beginning to See the Light.” She is also, as far as I know, the only person in the history of the world to appreciate the band Sweet Thursday, whom I shall now, finally, write about.

When Sanneh quotes Willis, she’s sounding a prescient warning about the deterioration of contexts for understanding popular music that he outlines throughout his piece. Rock and roll was being “co-opted by high culture,” as people–maybe exactly the kind of people who would want to read about pop music in The New Yorker–tried to separate the important stuff from the “merely commercial.” Apart from being an excellent point, this citation reminded me of one of Willis’s other reviews, which I had read in an anthology of her writing. The three albums under review in this particular piece were Abbey Road, The Velvet Underground, and something that I could not remember. I had to look it up; it turned out to be Sweet Thursday, the only album by Sweet Thursday, a band that nobody knows. I asked all of the people whom I thought might be old enough to know about them, and only my father-in-law had heard of them, and even he revealed later that hear of them was all he had done.

The accident of these nobodies (no offense) being in an article with two world-beating albums was interesting to me. Willis is not particularly nice or mean about the Beatles or the Velvets. Both of her analyses of them are largely founded on her understanding of them as developing some post-childhood sensibility. “For the first time in a long while,” she writes about Abbey Road, “the Beatles seem to have a real sense of themselves. They have transcended both pretentiousness and exaggerated simplicity, and have avoided moralizing about politics and pontificating about Indian philosophy.” This is a good drive-by attack on the White Album, and helps set up her later compliments to Abbey Road (including the observation that it’s “less smug” than Nashville Skyline, Bob Dylan’s 1969 effort). Her take on The Velvet Underground is to be surprised that they have traded in Delmore Schwarz and junkies for “Jesus, putting jelly on your shoulder, wearing your red pajamas, seeing the light, closing your door so the night will last forever, and stuff like that.” (That “stuff like that” is very funny to me). The last thing she says about the album is that “The Murder Mystery” is bad, a “pseudo-Frank Zappa thing” that is too long and which they should’ve put at the end of one of the album’s sides, so she could skip it.

You can see how the context is taking shape around these monumental albums–both the broad contexts in which the albums appear, and the specific context of Willis listening to the record. They are continuous: she makes the joke about “The Murder Mystery” being so bad and anticipates this becoming part of what we all know about the record, in the same way as part of what we all know about Abbey Road is that it performs a “real” version of the Beatles. Willis’s review is at an epistemological disadvantage, though, relative to the reader of today. She does not know that all three of these groups are going to be kaput by the end of 1970. (Apologies to Squeeze, the zombie-Velvets record with Doug Yule, but I am not counting it). She knows, of course, that the Beatles are famous, but the institutional position that both the Beatles and the Velvet Underground will eventually have could not be part of her thinking about them. And of course, she doesn’t know that no one will have heard of Sweet Thursday. She doesn’t know the context in which later readers will receive the famous bands, and that outside of my father-in-law having heard of them, Sweet Thursday will have no context at all. How, then, should someone today—in 2026—understand Sweet Thursday? What would it mean to make them the object of criticism, or even cognition?

The Other Sweet Thursday

I know that last bit is not true–other people know about Sweet Thursday–and I will come back to them, but first I want to go on a detour about their namesake. I really like giving myself homework: coming up with tasks, or task-like things I can do, that will be part of my various projects. One thing that I learned, in my scouring around for things to know about Sweet Thursday (band) and Sweet Thursday (album) is that they are named after Sweet Thursday (novel) by John Steinbeck. To return to a concept that I have used many times already in this essay, this novel is one that I had never heard of. It’s a sequel to Cannery Row, a novel by Steinbeck that I *had* heard of, and which I in fact believed myself to have read, but I was wrong. I read Tortilla Flat. (I’d read many others, too, but the one I specifically confused with Cannery Row was that one). Cannery Row and Sweet Thursday are about the same group of bums and sex workers and, also, a marine biologist named Doc, based on Steinbeck’s real-life friend Ed Ricketts.

Cannery Row ends with Doc, the main character, cleaning up after his disastrous party. He recites, or thinks, a poem called “Black Marigolds,” which was initially written in Sanskrit, which is about “savoring the hot taste of life.” Steinbeck wraps things up: Doc “wiped his eyes with the back of his hand. And the white rats scampered and scrambled in their cages. And behind the glass the rattlesnakes lay still and stared into space with their dusty frowning eyes.” Nature! Solitude! Poor Doc’s lonely resolution, after a bummy party! This is of a piece, I think, with the other Steinbeck I know–Tom’s ghostly loneliness at the end (or, toward the end, before he disappears) of The Grapes of Wrath, Kino getting rid of the pearl at the end of The Pearl, George doing what he does at the end of Of Mice and Men. Doc’s supreme loneliness has its objective correlative in the animals at his lab, and Cannery Row has a static and cohesive ending.

I hope it’s not too tortured an analogy to think about Cannery Row resembling Abbey Road or The Velvet Underground. Those are totemic albums, things that are situated into their contexts in a way that reshapes the landscape around them. Cannery Row is like that too: it has a unity of meaning that may resemble other Steinbeck novels, as I’ve noted above, but it has a particular kind of wholeness. The idle reader might mix it up with Tortilla Flat, but once you get straight what’s what, it has crisp edges: it’s a book about a lonely man who stays lonely. Abbey Road is about a band having fun one last time (sort of) before they implode. The Velvet Underground is about the development of Lou Reed’s writing, out from under John Cale’s drone-y stuff. I think these things are all true; but part of why I think they are true is because of the context for understanding them has always presented them to me with these ideas attached. If “The End” were (somehow) on the Help album, I don’t know if I could hear it the same way.

There is less critical context built up around Cannery Row than Abbey Road or The Velvet Underground, but there is some, and there is certainly some built around the kind of Steinbeck book that Cannery Row is. This is not true of Sweet Thursday; the kind of book Sweet Thursday is is a weird one. In Sweet Thursday, Doc gets involved in a romance plot. Steinbeck wrote the book at least in part because he thought that Rodgers and Hammerstein could turn it into a musical, which they did, and which not many people liked. A lot of what happens in the book is not obviously amenable to being in a musical. Doc has his love interest, Suzy, but they don’t interact all that much: Doc spends more time getting drunk over several chapters with a rich friend named Old Jingleballicks, and especially, he spends time trying to write a scientific paper called “Symptoms in Some Cephalopods Approximating Apoplexy.” There is a satisfying conclusion in which one of Doc’s friends breaks his arm, so that he’ll need help getting specimens to write the paper, and will have to get that help from Suzy, uniting the various threads. That part, I suppose, could make for an effective musical denouement; less so the business where the same friend is anxious because his horoscope says he’s doomed to become the President of the United States.

The least musical-theater element of Sweet Thursday comes from its most book-like quality: it’s John Steinbeck’s only novel with chapter titles; and the chapter titles are very explicitly referred to, in a prologue which, like the prologue to Part II of Don Quixote, features characters grappling with their literariness. “Suppose there’s chapter one, chapter two, chapter three,” says a leader among the bums named Mack, “That’s all right, as far as it goes, but I’d like to have a couple words at the top so it tells me what the chapter’s going to be about. Sometimes maybe I want to go back, and chapter five don’t mean nothing to me. If it was just a couple of words, I’d know that was the chapter I wanted to go back to.” So far so clear for Mack: he wants what we all want out of the thing around our texts (call it criticism), a help for understanding them. Steinbeck obliges his creature, sort of: the chapter titles are things like “Whom the Gods Love They Drive Nuts,” “There’s a Hole in Reality through which We Can Look if We Wish,” “Lousy Wednesday,” Where Alfred the Sacred River Ran,” and the big trio, “Sweet Thursday (I),” “Sweet Thursday (II)” and “Sweet Thursday Was One Hell of a Day.”

Sweet Thursday, that is, carries some form of its critical context on its back, like a hermit crab. Is it, to use Sanneh’s language, too nice? It’s certainly not mean; what I would call it is goofy. The shift from Cannery Row (which is not very goofy) to Sweet Thursday (which is) comes in large part from the wider social scope of the second book. There’s something sweet and goofy and non-stoic about Hazel worrying that he’ll have to become the president, or about Doc’s lonely genius being concretized into his paper about apoplectic cephalopods. But it’s also related to Mack’s idea that this writing should come with chapter titles and things like that that would allow him to go back to the writing when he needed it. Sweet Thursday needs this stuff–it’s a kind of exhausted novel (complimentary), and it has to make its own context to make up for that–and this is a goofy, idiosyncratic procedure. It’s the thing Sanneh is worried about: not that people are mean, but that there’s no clear “people” that we can apply a predicate to. “Mean” by Taylor Swift, he points out, directs Taylor’s terrible swift sword not at a Robert Christgau type, but just at some guy. Steinbeck’s book has some guys chattering about it happily all throughout. Can this help us understand Sweet Thursday, the album?

The Other Sweet Thursday

When Ellen Willis writes about Sweet Thursday (the album), she says that this band is the best new act since the Band. That’s nice! She says that four of the tracks (out of ten) make the uneven record “worth buying.” Okay! One of these songs, “Laughed at Him,” is “one of those wise-fool songs about a man who has seen too deeply to get along in ordinary society, but in spite of the trite theme it is very moving, mainly because of the singing and guitar work.” Tough but fair! She ends the review by saying that she hopes the group will tour the United States soon, and that she suspects that they are fantastic performers. As far as I can tell, they never did. For whatever reason, Robert Christgau seemed to know that Sweet Thursday was not long for this world: his review, which came out only five days later, is, in its entirety, “An honest, listenable record from an English group that may well never make another.”

When Willis writes that “After Hours” sounds childish, she is still interested in it at least in part because she knows that it’s written by the man who wrote “Heroin” and “All Tomorrow’s Parties.” When I think about “After Hours,” it’s informed by not only that, but the fact that the man who wrote it would go on to write “Street Hassle” and “Open House” and “Junior Dad.” What should inform my interest in “They Laughed At Him” by Sweet Thursday is really nothing at all.

What did I think of Sweet Thursday? I liked it a lot. I have been listening to it for months, while I have been trying to organize my thoughts about all of this stuff. I thought more of the songs made the album worth buying than Willis did. I recognized a mishmash of other bands that the songs reminded me–very early Pink Floyd on “Cobwebs,” Between the Buttons-era Rolling Stones on “Molly,” Procul Harum on “Sweet Francesca.” On that one they also sing some goofy lyrics about Frodo and Uncle Tom’s cabin. A not very helpful thought that I kept having was that nearly every song sounded like it could have been on some Wes Anderson soundtrack or other–especially “Laughed at Him,” the wise-fool song that Willis kind of makes fun of, which has a pleasantly dinky clavichord part. “Dealer” doesn’t sound like much of anything in particular, though I like it a lot and it has a big tympani noise on the chorus.

These are not the most organized thoughts, honestly, despite the large amount of time I have spent listening to and thinking about this album since I refamiliarized myself with the name of it a few months ago. That is to say: devoid of a public context for understanding this album, the thing I’d have a very strong version of for Abbey Road or The Velvet Underground, I’m left to my own devices. Sweet Thursday doesn’t do much the way that Steinbeck’s Sweet Thursday does, either–the album doesn’t contextualize itself. What I am left with is a combination of relief and gratitude. I am relieved that not all music is like this–although Sanneh is right to be anxious that it’s waning, there still are localized critical communities that share the contexts for the work that they care about; and the possibility exists, still, to make a new one. And I am grateful that some music is like this–that there are new things, even new old things, to discover and think about. It would be goofy–in the style of Steinbeck’s Mack–for me to try to, all on my own, insist upon a new overweening context in which to understand Sweet Thursday, to claim something like “Sweet Francesca” is actually better and more significant than “Whiter Shade of Pale” (it’s not). But I don’t have to do that, because I can make a smaller claim; I can tell you hey, listen to this. We can think together about a context that might have Sweet Thursday in it. Some of their songs are pretty good.